Timisoara_Med 2022, 2022(2), 6; doi:10.35995/tmj20220206

Article

Mobile Technology Patterns in Dentistry Students. A Clinical Survey

1

Department of Prosthodontics, Faculty of Dental Medicine, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania; codrutaille@yahoo.com (C.G.); ajivanescu@yahoo.com (A.J.)

2

Center for Modeling Biological Systems and Data Analysis, Department of Functional Sciences, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania; dlungeanu@umft.ro

*

Correspondence: lucianag@umft.ro

How to cite: Goguță, L.; Lungeanu, D.; Gruia, C.; Jivănescu, A. Mobile Technology Patterns in Dentistry Students. A Clinical Survey. Timisoara Med. 2022, 2022(2), 6; doi:10.35995/tmj20220206.

Received: 6 October 2022 / Accepted: 20 November 2022 / Published: 8 December 2022

Open access

: TIMISOARA MEDICAL JOURNAL is a peer-reviewed open-access journal.Abstract

:(1) Introduction: Information technology is seen as instrumental in shifting the paradigm of teaching and learning towards active learning. Students and young professionals have been suggested as being more prone to mobile technology addiction compared to the general population, with profession-characteristic patterns and possible consequences for long-term professional development. (2) Materials and methods: An original questionnaire was developed to assess the attitude towards mobile technology in active learning in a dental school in Romania. The study was conducted among 214 students in dentistry to identify any possible patterns of using mobile devices. Consistency analysis was conducted on the closed-ended questions by employing the reliability Cronbach’s alpha. Furthermore, inter-item correlation and principal components analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation was conducted to investigate the underlying motivational framework in the use of the internet. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were applied to verify the data suitability for factor analysis. (3) Results: Principal component analysis and subsequent K-means clustering were applied on the data, leading to the conclusion that the underlying motivation of frequent use within these youngsters is mostly rooted in their professional interests, rather than compulsive or social pressure. For the two resulting clusters, the R-scores proved to be significantly different, with a median (IQR) of 43 (41–47) and 48 (44–54) for the first and the second cluster, respectively (Mann–Whitney U test, p < 0.001). Statistical analysis was conducted on de-identified data using SPSS v.20 and the R v.3.4 software packages, with a 0.05 level of significance. (4) Conclusion: The increasing need of constant network connection comes from the high pressure of the professional environment. This study results provide data grounds for diagnosing a possible behavioral addiction syndrome, which certainly is an intrinsic part of our ordinary life, both in professional and leisure activities.

Keywords:

mobile technology; internet use; medical education; behavioral addictionIntroduction

Academic education has a long history of excellence and an ability to adapt to the continual challenges of societal evolution. While preparing professionals for this very society is non-trivial in itself, the career paradigms also undergo highly dynamic transformation. Medical education faces specific challenges on top of the difficulties it shares with the university system in general [1].

Internet and mobile technology are harnessed to implement new approaches in medical education, such as active or blended learning, and mixing Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) with traditional education [2,3,4,5,6,7].

In contrast to the initial enthusiasm regarding these new approaches and certainly positive learning experiences, such unconventional methods in education also faced concerns regarding their appropriateness or effectiveness in preparing for the medical profession and national examinations [2,8]. Such dissatisfaction brings forward the issue of assessment and grading associated with new educational approaches.

It has been demonstrated that professors need training workshops to ensure that students are not only accessing evidence-based information but can differentiate between evidence-based and non-evidence-based information app. The tutors in this study also require information on how to provide their students with advice on using mobile technology. Institutions involved with clinical dentistry should acknowledge such challenges [9], and designing learning materials and applications for mobile devices may increase students’ performance [10].

A surprise appeared during the COVID-19 pandemic situation, when dental students were generally unhappy with the interruption of traditional education caused by COVID-19 and having to continue their education online [11,12,13,14].

Apart from these pros and cons regarding the foreseen benefits of mobile technology, a new addiction has emerged, i.e., internet addiction (IA), and little is known about its pathophysiological and cognitive mechanisms. There is still too little research focused on this area with highly dynamic evolution, though it has gradually become an issue in public health. Inspired by other behavioral addiction forms, the IA models share some existing diagnosing criteria (e.g., loss of control over its use) leading to psychological, social, and professional conflicts or problems, such as those in mood management, tolerance, withdrawal, and craving/anticipation [15,16].

Identifying students with potential IA is an additional issue, for it usually co-exists with a variety of psychological or even psychiatric disorders [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Standardized addiction tests and subsequent therapy have been put forward as possible solutions to IA [23]. Moreover, around the world from Europe to Asia, medical students were suggested as being more prone to IA compared to the general population, [24] with a large variety of associated risk factors [25,26].

Effective countermeasures, prevention strategies, and evidence-based treatments have not been identified or accepted, with the possible addiction being mostly qualitatively described, and with interventions focusing on group counseling programs, cognitive behavioral therapy, and sports [27]. Recent reports about mobile technology impeding on carrying out ordinary professional activities were even more worrying [28,29].

A legitimate question arises: if mobile technology is dangerous as potential harms to our personalities’ nature and our social beings, how come it has not been banned, as addictive substances are prohibited? How could a medical professional gain enough experience with technology to be effective in everyday tasks, and how much is too much? While many efforts have been focused on pinpointing the addiction, we know little about the using patterns of mobile technology in everyday professionals’ activity.

Education is supposed to balance two contrary directions: (a) to employ the mobile technology for its positive potential in education and specific instruments invaluable to implementing new teaching, learning, and assessment approaches; (b) to design and effectively apply mobile technology (social media)—preventive strategies at least during clinical work. Taking both views into consideration, we designed an original questionnaire from scratch, aimed at collecting information about the actual use of mobile technology, rather than making judgments, diagnoses, or any sort of classification. The aim of the study was to find out the patterns of mobile technology use by dentistry students (courses, clinical work, learning, socializing with teachers and colleagues) and how mobile technology use is affecting them during resting and sleeping.

Materials and Methods

This original cross-sectional study was conducted in the Faculty of Dentistry, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania, between 2020 and 2022. The whole university employed on-line courses during the pandemic (COVID-19) situation and classical lecture-courses in 2022, accompanied with supervised practical classes. The Ethical Committee of the University approved the study, and a total of 214 participants were included (117 females and 97 males). Two inclusion criteria were applied: (1) the participant was a student in dentistry, and (2) she/he engaged to respond to the whole questionnaire. The exclusion criterion was not responding to all questions. Each participant signed informed consent and a personal data privacy form. A total of 3 of the 217 participants initially enrolled did not respond to all questions, so they were excluded from the final data processing, and no imputation was applied to the raw data.

The questionnaire consisted of 28 questions: closed-ended questions rated on a five-point Likert-type scale were asked, except for the non-rating closed questions at the beginning (Q1, Q3, and Q4) and the last open question (Q28) (Supplementary Table S1). The concept of these questions was the result of an observation of the students’ and young residents’ behavior during the courses and during the clinical work on patients.

Univariate descriptive statistics were performed to describe respondents’ demographic characteristics and declared non-ranking preferences for Internet use.

Consistency analysis was conducted on the closed-ended questions by employing the reliability Cronbach’s alpha. The standardized Cronbach’s alpha was provided as well as an indication of non-redundancy when the two values were close.

Furthermore, inter-item correlation and principal components analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation was conducted to investigate the underlying motivational framework in the use of mobile technology. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were applied to verify the data suitability for factor analysis. The scree plots and eigenvalues over 1 were considered as criteria for deciding the appropriate number of factors to be extracted. Based on PCA-extracted factors, the K-means clustering was conducted, with k = 2.

For each participant, a final comprehensive score was calculated, and a summative analysis was performed with univariate non-parametric statistical testing.

Statistical analysis was conducted on de-identified data using SPSS v.20 and the R v.3.4 software packages, with a 0.05 level of significance.

Results

The age of the 214 the respondents was between 21 and 25 years, with a mean (Standard Deviation) of 24.17 (4.07). All participants declared to have and use a mobile phone with Internet access.

A comprehensive scoring frame named “R-scores” was proposed for the questionnaire’s answers, aimed at favoring the moderate use of mobile technology, and penalizing not only any possible addictive behavior, but also the lack of interest in mobile instruments (Table 1). The R-scores showed no differences between the two genders, with a median (IQR) of 45 (42–48) and 44 (42–47) for the females and males, respectively (Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.513).

Table 1.

The R-scores as a rating frame of the internet and mobile technology use.

| Questions | Scoring points |

|---|---|

| Q2, Q5–Q25 | Never—Almost never— Sometimes— Often— Very often 2—1—1—3—3 |

| Q3 | Books— Internet— Dentistry Journal—Ask the teacher 1—1—1—1 |

| Q4 | E-mail—SMS—Mobile phone—WhatsApp—Messenger 1—1—1—2—2 |

| Q26, Q27 | Never—Almost never—Sometimes—Often—Very often 3—2—2—1—1 |

| Q28 | 1 if a site was mentioned |

The K-means clustering made use of the eight PCA factors previously extracted: factor 3, 5, 6 and 7 proved to be significant in this classification (Table 2).

Table 2.

The K-means clustering by employing the eight PCA factors extracted.

| Factor score | Cluster Mean Square (1 df) | Error Mean Square (212 df) | F-Statistic (1, 212 df) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Posting need | 0.930 | 1.000 | 0.929 | 0.336 |

| 2 Emotional | 0.421 | 1.003 | 0.420 | 0.518 |

| 3 Professional | 80.893 | 0.623 | 129.813 | < 0.001 ** |

| 4 Connected | 1.429 | 0.998 | 1.432 | 0.233 |

| 5 Needless/pointless | 11.721 | 0.949 | 12.345 | 0.001 ** |

| 6 Specific use | 30.464 | 0.861 | 35.381 | < 0.001 ** |

| 7 Frequent use | 12.061 | 0.948 | 12.725 | < 0.001 ** |

| 8 Socializing means | 0.675 | 1.002 | 0.674 | 0.413 |

df—degrees of freedom; ** statistically high significance (p < 0.01).

For the two resulting clusters, the R-scores proved to be significantly different, with a median (IQR) of 43 (41–47) and 48 (44–54) for the first and the second cluster, respectively (Mann–Whitney U test, p < 0.001).

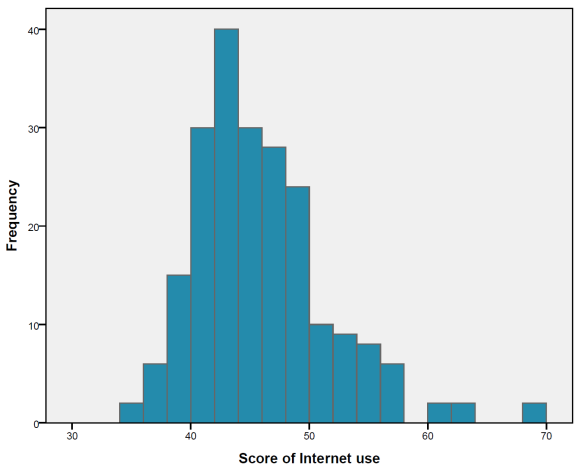

The distribution of the internet use/question frequency is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Score of internet use/question frequency.

Most of the cumulated points for the Likert-type scale questions suggest moderation in mobile technology use among the participants, with high scores and highly significant correlations related to their profession and professional interests. When observed with their inter-item correlation values and PCA loadings, clear patterns of these scale-scores emerge: although high, scores for Q2 (How often do you use a mobile phone for social media access?) do not strongly correlate with any other item, even if it is significantly correlated with many. When considering the factors, Q2 brings a positive contribution to factors 6 (Specific use) and 7 (Frequent use), with an overall contribution to the comprehensive picture. On the other hand, Q26 (Are you searching for Dentistry (e.g., practical aspects) on YouTube on your mobile phone?) and Q27 (Are you looking for articles related to Dentistry on the Internet accessing your mobile phone?) have high cumulated scale-scores, and they strongly and significantly correlate with each other, both strongly contributing to factor 3 (Professional), a decisive discriminator in K-means clustering. Questions Q10 (In your friends’ list, do you have people you do not interact with?) and Q18 (Have you ever regretted using your mobile phone for long?) added up to high scale-scores and have important contribution not only to factor 3 (Professional), but also to factor 5 (Needless/pointless), a significant discriminator as well. This latter contribution suggests a self-awareness of the importance of focused use and a refrain from wasting time. Moreover, Q17 (Do you have used your phone longer than intended?) and Q13 (Have you ever experienced sleep deprivation because of these applications?) have relatively high scale-scores and they strongly correlate with each other, with Q17 negatively contributing to factor 5 (Needless/pointless). Item Q14 (Do you use mobile applications to pass time?) resulted in high scale-scores, but it did not correlate with any other item.

The important difference between the two clusters of mobile technology users among the dental students would come from their patterns of professional motivation, rather than frequency of use or compulsive need to have constant net connection. Moreover, apart from the resulting two clusters of users among the young dentists, their preferences towards Internet as a source of professional information are compelling: 78% would prefer to look on the Internet on their mobile phones, rather than asking a teacher or searching in a traditional book, and almost 60% have a preferred medical site. The number one site used by the dentistry students and young dentists was PubMed.

Discussion

The pattern of usage of mobile phones among dental students showed an alarming indication that students have been addicted to mobile phones, which in turn affects their academic performance in a negative way [30]. Recent studies showed that 25% of medical students presented net addiction [31,32,33,34], while another study showed that dental students who have high levels of smartphone addiction or high perceived stress levels experienced poor sleep quality. Identifying smartphone addicts amongst students as well as stressors are imperative measures to allow timely assistance and support in the form of educational campaigns, counselling, psychotherapy, and stress management [35]. Smartphone usage was positively associated with dental students’ academic performance. Importantly, a small number of students were identified as suffering from smartphone addiction [36]. The high prevalence and usage of mobile internet connectable devices as well as the high availability of the internet may indicate a tendency toward mobile learning [37]. The present study concluded that all the dentistry students included in the study are using mobile technology in their school and private life, but a real addiction to mobile technology has not been found.

Problematic mobile phone users received significantly higher scores for depression severity, bodily pain, and daytime sleepiness. Health problems were significantly more severe among female medical students, indicating poorer sleep quality [38,39]. Scores for sleep problems were low in the present study, showing that western Romanian dental students are not encountering sleep problems currently.

Recent studies are showing that higher smartphone addiction scores have a negative impact on interpersonal communication and social life and reduce learning efficacy in students. Therefore, students and lecturers should be better informed regarding the benefits and risks of smartphone use in education, with precautions provided against excessive and needless use [33,34,35,40].

The study limitations are related to the single site study population and the relatively small sample of subjects questioned.

Conclusions

Within the limits, the study provides data grounds for diagnosing a possible behavioral addiction syndrome, which certainly is an intrinsic part of our ordinary life, both in professional and leisure activities. Mobile technology is present in the everyday life of the dentistry students included in this study. The increasing need for constant network connection comes from the high pressure of the professional environment and the need for interaction with peers. Instruments for diagnosing the addictive use of mobile technology should be continuously adapted to the pressure of the professional environment.

Supplementary Materials

The following file is available online at https://journals.jams.pub/user/manuscripts/displayFile/23e5791339c756dab42decd528da07b3/supplementary.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank to all the students who accepted to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G., C.G.; Methodology D.L.; Validation, D.L., A.J. and L.G.; Formal Analysis, D.L.; Investigation, C.G.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, D.L.; Writing—Review and Editing, L.G.; Visualization, L.G.; Supervision, A.J.; Project Administration, L.G.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Taylor, D.; Hamdy, H. Adult learning theories: Implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Med Teach. 2013, 35, e1561–e1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chingos, M.M.; Griffiths, R.J.; Mulhern, C.; Spies, R.R. Interactive online learning on campus: Comparing students’ outcomes in hybrid and traditional courses in the university system of Maryland. J. High. Educ. 2016, 88, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordy, X.Z.; Zhang, L.; Sullivan, A.L.; Bailey, J.H.; Carr, E.O. Teaching and learning in an active learning classroom: A mixed-methods empirical cohort study of dental hygiene students. J. Dent. Educ. 2019, 83, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, J.L.; Suresh, V.; Bittar, P.; Ledbetter, L.; Mithani, S.K.; Allori, A. The utilization of video technology in surgical education: A systematic review. J. Surg. Res. 2019, 235, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loes, C.N.; Culver, K.C.; Trolian, T.L. How collaborative learning enhances students’ openness to diversity. J. High. Educ. 2018, 89, 935–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutinan, S.; Riedy, C.A.; Park, S.E. Student performance in a flipped classroom dental anatomy course. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2018, 22, e343–e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzstein, R.M.; Roberts, D.H. Saying goodbye to lectures in medical school - paradigm shift or passing fad? N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walling, A.; Istas, K.; Bonaminio, G.A.; Paolo, A.M.; Fontes, J.D.; Davis, N.; Berardo, B.A. Medical student perspectives of active learning: A focus group study. Teach. Learn. Med. 2016, 29, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, B.; Hill, K.; Walmsley, A.D. Mobile learning in dentistry: Challenges and opportunities. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 227, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suner, A.; Yilmaz, Y.; Pişkin, B. Mobile learning in dentistry: usage habits, attitudes and perceptions of undergraduate students. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarialioglu Gungor, A.; Sesen Uslu, Y.; Donmez, N. Perceptions of dental students towards online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Oral Res. 2021, 55, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbay, Y.; Cirakoglu, N.Y. Evaluation of distance learning and online exam experience of Turkish undergraduate dental students during the Covid-19 pandemic. Niger. J. Clin. Pr. 2022, 25, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badovinac, A.; Par, M.; Plančak, L.; Balić, M.D.; Vražić, D.; Božić, D.; Musić, L. The Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dental education: An online survey of students’ perceptions and attitudes. Dent. J. 2021, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şavkın, R.; Bayrak, G.; Büker, N. Distance learning in the COVID-19 pandemic: Acceptance and attitudes of physical therapy and rehabilitation students in Turkey. Rural Remote Health 2021, 21, 6366. [Google Scholar]

- van Rooij, A.J.; Prause, N. A critical review of “Internet addiction” criteria with suggestions for the future. J. Behav. Addict. 2014, 3, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Khan, A.M.; Rajoura, O.P.; Srivastava, S. Internet addiction and its mental health correlates among undergraduate college students of a university in North India. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2018, 7, 721–727. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, C.-H.; Yen, J.-Y.; Yen, C.-F.; Chen, C.-S.; Chen, C.C. The association between Internet addiction and psychiatric disorder: A review of the literature. Eur. Psychiatry 2012, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, D.-D.; Chai, J.-X.; Wang, D.; Li, M.S.; Zhang, L.; Lu, L.; Ng, C.; Ungvari, G.S.; Mei, S.-L.; et al. Prevalence of Internet addiction disorder in Chinese university students: A comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molavi, P.; Mikaeili, N.; Ghaseminejad, M.A.; Kazemi, Z.; Pourdonya, M. Social anxiety and benign and toxic online self-disclosures: An investigation into the role of rejection sensitivity, self-regulation, and Internet addiction in college students. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2018, 206, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, R. Internet addiction and psychological well-being among college students: A cross-sectional study from Central India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2018, 7, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, J.-Y.; Ko, C.-H.; Yen, C.-F.; Wu, H.-Y.; Yang, M.-J. The comorbid psychiatric symptoms of internet addiction: attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, social phobia, and hostility. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, F.; Halawi, G.; Jabbour, H.; El Osta, N.; Karam, L.; Hajj, A.; Khabbaz, L.R. Internet addiction and relationships with insomnia, anxiety, depression, stress and self-esteem in university students: A cross-sectional designed study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.-J.; Zheng, T.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Yao, Y.-S. Internet addiction detection rate among college students in the People’s Republic of China: A meta-analysis. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2018, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücens, B.; Üzer, A. The relationship between internet addiction, social anxiety, impulsivity, self-esteem, and depression in a sample of Turkish undergraduate medical students. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 267, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.W.B.; Lim, R.B.C.; Lee, C.; Ho, R.C.M. Prevalence of internet addiction in medical students: A meta-analysis. Acad. Psychiatry 2018, 42, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateno, M.; Teo, A.R.; Shiraishi, M.; Tayama, M.; Kawanishi, C.; Kato, T.A. Prevalence rate of Internet addiction among Japanese college students: Two cross-sectional studies and reconsideration of cut-off points of young’s Internet addiction test in Japan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 72, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.-Q.; Yao, N.-Q.; Zhou, X.; Liu, J.; Lv, Z.-T. The association between attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and internet addiction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Nie, J.; Wang, Y. Effects of group counseling programs, cognitive behavioral therapy, and sports intervention on internet addiction in East Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2017, 14, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loredo, E.; Silva, M.P.; de Souza Matos, B.D.; da Silva, E.O.; Lucchetti, A.L.G.; Lucchetti, G. The use of smartphones in different phases of medical school and its relationship to Internet addiction and learning approaches. J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhayay, N.; Guragain, S. Internet use and its addiction level in medical students. Adv. Med Educ. Pract. 2017, 8, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.; Patthi, B.; Singla, A.; Gupta, R.; Saha, S.; Kumar, J.K.; Malhi, R.; Pandita, V. Nomophobia: A Cross-sectional Study to Assess Mobile Phone Usage among Dental Students. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, ZC34–ZC39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaie, H.; Lebni, J.Y.; Abbas, J.; Mahaki, B.; Chaboksavar, F.; Kianipour, N.; Toghroli, R.; Ziapour, A. Internet Addiction Status and Related Factors among Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in Western Iran. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmadhikari, S.P.; Harshe, S.D.; Bhide, P.P. Prevalence and Correlates of Excessive Smartphone Use among Medical Students: A Cross-sectional Study. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2019, 41, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, J.R.; Beverly, E.A. Burnout, Perceived Stress, Sleep Quality, and Smartphone Use: A Survey of Osteopathic Medical Students. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2020, 120, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanusi, S.Y.; Al-Batayneh, O.B.; Khader, Y.S.; Saddki, N. The association of smartphone addiction, sleep quality and perceived stress amongst Jordanian dental students. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 26, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafla, A.C.; Herrera-López, H.M.; Eraso, T.F.; Melo, M.A.; Muñoz, N.; Schwendicke, F. Smartphones addiction associated with academic achievement among dental students: A cross-sectional study. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 85, 1802–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erb, J.; Harder, M.; Zitzmann, N.U.; Filippi, A. Lernen im Zahnmedizinstudium Learning while studying dentistry. Swiss Dent. J. 2021, 131, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, K.C.; Wu, L.H.; Lam, H.Y.; Lam, L.K.; Nip, P.Y.; Ng, C.M.; Leung, K.C.; Leung, S.F. The relationships between mobile phone use and depressive symptoms, bodily pain, and daytime sleepiness in Hong Kong secondary school students. Addict. Behav. 2020, 101, 105975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, A.; Cheema, M.K.; Naseer, M.; Javed, H. Comparison of quality of sleep between medical and non-medical undergraduate Pakistani students. J. Pak. Med Assoc. 2018, 68, 1465–1470. [Google Scholar]

- Celikkalp, U.; Bilgic, S.; Temel, M.; Varol, G. The Smartphone Addiction Levels and the Association With Communication Skills in Nursing and Medical School Students. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 28, e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2022 Copyright by the authors. Licensed as an open access article using a CC BY 4.0 license